Yinka Shonibare

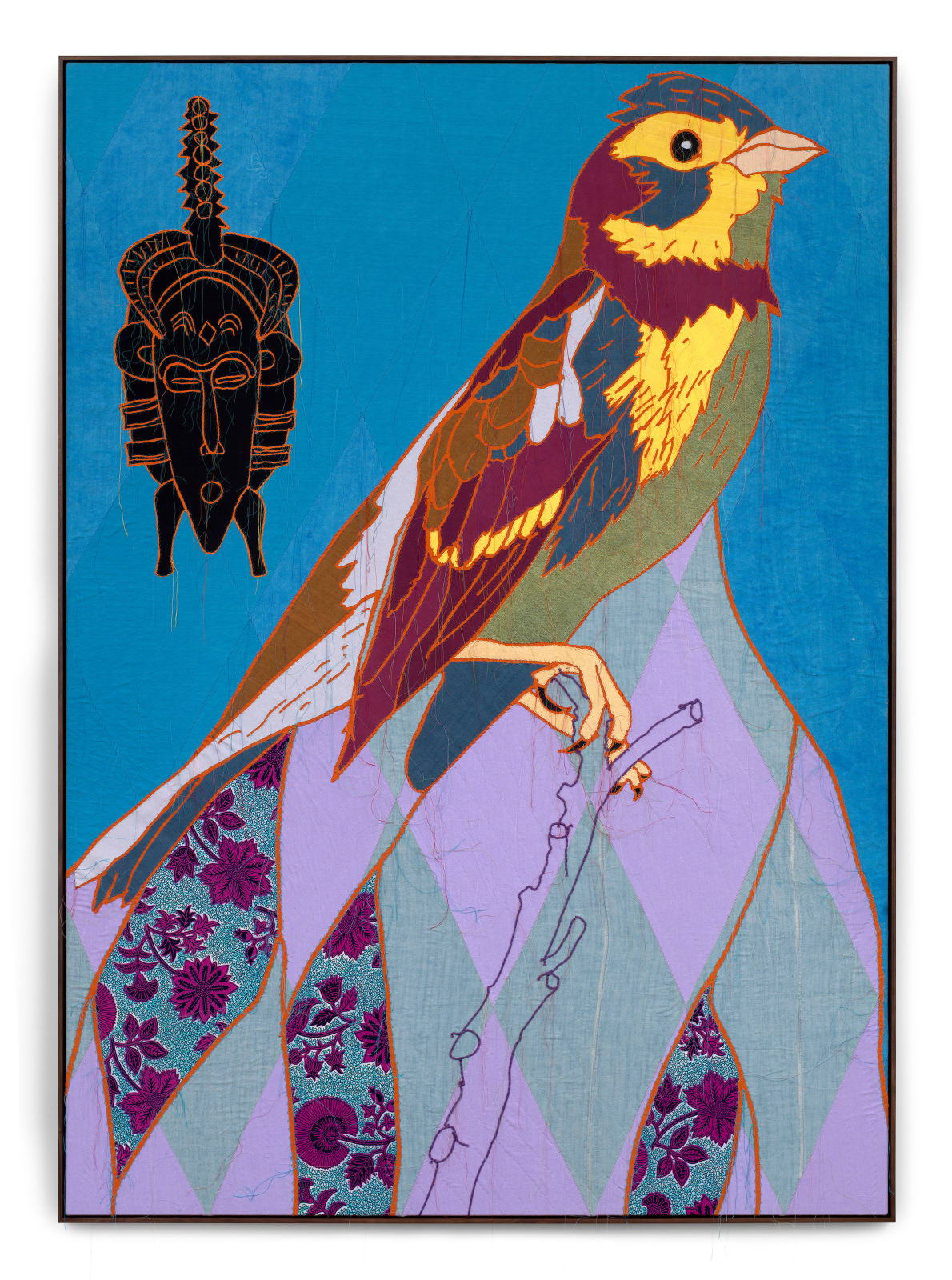

Yinka Shonibare’s practice involves creating patterned wax prints on cotton fabrics, which he exhibits in a wide range of forms including stretched canvases, book covers, and clothing for the figures in his sculptural installations. Shonibare’s designs are characterised by bright, bold, and deep colours, often depicting natural forms such as wood, earth, animals, flowers, and shapes inspired by microscopic cells and other lifeforms. By using these forms, he situates his practice between nature and culture, while also highlighting the ways identity can be represented through motifs and material choices.

Shonibare’s practice explores colonialism, race, and class. His work interrogates how these concepts have shaped both his personal and wider community’s identities. Shonibare is inspired by his own life experiences as a British-Nigerian artist, as well as by his experiences of wider world events that he is exposed to through the media. Using both and global perspectives allows him to situate his art within broader conversations about inequality, class, and the effects of colonialism. This makes his practice not only aesthetics-based but also political through using visual languages.

Detail of British Library, Yinka Shonibare, 2014

Shonibare’s textile-based works resonate strongly my own practice. I have focused on using batik techniques, and the Dutch wax printing method that Shonibare uses has historical ties to Indonesian batik. Dutch merchants in the nineteenth century, inspired by traditional Indonesian designs, attempted to mass-produce wax-resist textiles for Southeast Asian markets but they also became popularised in West African cultures, where they were reinterpreted and transformed into symbols that those cultures better identified with. Shonibare’s use of these fabrics therefore represents a history of cultural exchange, colonial connections, and adaptation of an artform. In my own practice, I have experimented with similar techniques, and I find it inspiring that Shonibare often uses multiple individual prints to create larger artworks – which I also experimented with by combining smaller batik pieces into a larger composition for my MA show artwork ‘Green 116’.

Although my practice does not directly explore the themes of colonialism, race, and class, I believe there is a strong connection between Shonibare’s work and my own. Colonialism has not only shaped human societies but has also influenced the natural world in various ways, with the natural world being the central focus of my practice. Environmental historian Richard Grove (1995) states that “Colonialism was not only about the domination of peoples, but also about the domination of ecosystems. Forests were cleared, species were hunted to extinction, and landscapes were reshaped to serve imperial economies.” This shows how the protections of both human rights and the natural world are interconnected. Malcom Ferdinand (2019) also states that “Colonialism racialized both people and environments, producing hierarchies where certain landscapes and bodies were deemed productive, while others were cast as waste or wilderness.” which further shows how both people and various aspects of nature have both been marginalised throughout history. These perspectives resonate with my own practice, which seeks to explore the relationship between humans and the natural environment.

Reflecting on Shonibare’s work has encouraged me to consider the potential for both intentional and unintentional symbolism within my own practice. For example, I have begun to ask myself what roles the plants and animals I include in my work play in my life, and what meanings they have been given historically. In many cultures, specific plants and animals are associated with particular values, myths, or identities. By incorporating them into my batiks, I can engage with these symbolic meanings. This has prompted me to think more critically about the choices I make in my practice, and how audiences might interpret them.

As a result of this reflection, my work has begun to change. I have moved toward creating batiks that are less focused on detail and instead make greater use of non-distinct lines and shapes. This allows audiences more freedom to project their own interpretations onto each piece, rather than being guided by specific imagery. In doing so, I hope to create a more open-ended dialogue between the work and its viewers, encouraging them to reflect on their own relationships with nature and history.

Another area I am interested in developing is the scale and format of my batiks. Up to now, my works have mostly kept to a near-uniform size of approximately 30x30cm squares. While this consistency has allowed me to explore repetition and variation, I believe experimenting with different sizes and shapes could open up new possibilities for display and interpretation. For example, batiks could be hung from different lengths of wire, allowing their unique extremities to be emphasised and creating dynamic installations that interact with space. Larger pieces could invite viewers to immerse themselves more fully, while smaller works might encourage more intimate engagement. By varying the scale of my batiks, I can expand the scope of my practice and explore how form and presentation shape meaning.

In addition to experimenting with scale, I plan to explore different material processes. Specifically, I want to experiment with varying ratios of soy, paraffin, and beeswax in my batiks. Each type of wax has distinct properties that affect how the dye interacts with the fabric, and by adjusting the ratios I can achieve different effects. Stronger dyes could allow for deeper, brighter colours, while certain wax combinations might produce bolder, more distinct lines and shapes. These technical experiments are not only about the aesthetics of my work - they are also about expanding the expressive potential of my practice.

Researching Shonibare’s practice has shown me how using textiles can have a strong connection to identities and history. Although my own focus is on the natural world rather than directly on colonialism, race, and class, I see our practices as connected. Both of us are concerned with how history can shape the present, and how art can be used for reflection and dialogue. By learning from Shonibare’s approach, I have been able to expand my own practice, both conceptually and technically.

In conclusion, Shonibare’s use of patterned wax prints highlights the complex histories embedded in textiles, while his exploration of colonialism, race, and class situates his work within contemporary debates. My own practice, while focused on nature, resonates with his in its engagement with history and symbolism. Through reflection on his work, I have begun to consider the meanings of the plants and animals I depict, to experiment with less detailed and more open-ended forms, and to explore new possibilities in scale and material processes. These developments mark an important evolution in my practice, one that is enriched by dialogue with Shonibare’s art and by critical engagement with the broader histories of colonialism and the environment. In this way, my work continues to grow, shaped by both personal exploration and the wider cultural conversations that it can participate in.

Grove, R. (1995) ‘Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860’, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press

Ferdinand, M. (2019) ‘Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World’, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons

Tate. Yinka Shonibare CBE [Online]. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/yinka-shonibare-cbe-3081 (accessed on 28/10/25)

African Bird Magic (Yellow Breasted Bunting) II, Yinka Shonibare, 2023

African Bird Magic (Crested Lark) I, Yinka Shonibare, 2023

How Does a Girl Like You Get to Be a Girl Like You?, Yinka Shonibare, 1995

Olga Prinku

Olga Prinku’s practice focuses on botanical embroidery, a technique that involves weaving and stitching dried and preserved flowers, twigs, berries, and other plant materials into tulle netting. This process allows her to create both curated floral-patterned tapestries and entirely new designs, such as landscapes or animal forms, that push embroidery beyond its traditional boundaries. Because the tulle netting she uses is almost invisible and does not cast a shadow, the botanical objects can appear to be suspended in the space, giving her work an ethereal quality. Prinku considers the role of light in her displays. She considers how the shadows cast by the flowers and plants can add further depth and dimension, transforming her pieces into immersive experiences that shift depending on the environment they exist in at the time. This sensitivity to material and presentation demonstrates how her practice is not only about craft but also about creating atmospheres that invite viewers to reflect on nature’s fragility and resilience.

Prinku herself states, “I see my artistic work as both homage and inquiry, honouring the beauty and strength of the natural world while reflecting on our relationship with it. Each piece is a meditation on growth, fragility and transformation, and the creative human capacity to shape meaning with the simplest of materials.” This statement highlights the duality of her practice: her work is both a celebration of nature’s beauty and a reflection on how humans interact with and reinterpret the natural world. It connects closely to my research into the practice of Yinka Shonibare, as both artists investigate the concept of human intervention in nature, though they approach it in very different ways. Where Shonibare uses Dutch wax prints to interrogate colonial histories and cultural meanings, Prinku works with foraged natural materials to explore fragility, transformation, and the cycles of growth and decay. Both artists, however, share an interest in how materials themselves carry meaning, and how those meanings can be reimagined through artistic practice.

Whispers, Olga Prinku, 2024

Shadow cast by Whispers, Olga Prinku, 2024

Prinku’s choice of materials and the way she uses them resonates strongly with my own practice. I have also worked with natural materials, particularly through the use of natural dyes and textiles, which similarly root my work in the organic world. Like Prinku, I make use of embroidery frames and hoops, though in my case they are part of the process of creating batik paintings on cotton fabric. This parallel in process highlights how different practices can share structural similarities even when the outcomes are visually different.

Her practice developed out of her appreciation for the natural world around her, and this is something I can relate to. The natural world has also been a source of inspiration in my own work, shaping not only the imagery I use but also the materials and processes I choose. Like Prinku, I am interested in how natural materials can be transformed into something new, while still being representative of their origins. Creating something out of organic matter is a way of appreciating nature while also reimagining it through the use of human creativity. This approach situates both of our practices within a broader tradition of artists who use natural materials not simply for their aesthetic qualities but also for their symbolic and conceptual resonance.

The Wainwright Prize (2023) writes “Prinku’s work embodies the artistry we find in the natural world every day, as well as nature’s creative potential to enrich and make up our own creative practices.” This observation captures the essence of her approach: she works almost exclusively with found and foraged natural materials, with the only exceptions being the tulle netting and tools she uses as a base. This near-exclusive use of natural materials shows her commitment to working in with the environment. It also highlights how her work is not only about representation but also about process - gathering, preserving, and arranging materials in ways that reflect both her personal vision and the qualities of the plants themselves.

Looking at Prinku’s work has encouraged me to think more deeply about the significance of the materials I use in my own practice. It has made me question whether the papers and fabrics I draw and paint on have any connection to the plants and animals I depict. For example, “Does the insect I have drawn ever encounter the species of flower that was recycled to make this paper in the wild?”.

As a result of researching Prinku’s practice, I have been inspired to expand my own methods by incorporating embroidery and stitching into my paintings and drawings. I see this as a way of adorning my work, adding texture and depth, and creating a connection between different techniques.

This research has encouraged me to reflect on how I might achieve similar outcomes in my own practice. By paying closer attention to the origins and associations of my materials, and by experimenting with new techniques such as embroidery, I hope to create work that is both visually engaging and conceptually rich, resonating with audiences on multiple levels.

In conclusion, Olga Prinku’s botanical embroidery highlights the beauty and delicateness of the natural world while also prompting reflection on our relationship with it. Her practice has been a source of inspiration for me, encouraging me to reconsider the materials and processes I use, and the meanings that can be represented through my work. By learning from her approach, I have been able to expand my own practice, and to use it as part of a dialogue about art, nature, and human creativity.

Wainwright Prize. Introducing Olga Prinku & The Art of Flowers-on-Tulle Embroidery [Online]. Available at: https://wainwrightprize.com/news/olga-prinku/? (accessed on 31/10/25)

Prinku, O. Olga Prinku [Online]. Available at: https://www.prinku.com/ (accessed on 02/11/25)

Prairie Birds, Olga Prinku, 2019

Seedheads at Hidcote, Olga Prinku, 2024

Hedge at Hidcote, Olga Prinku, 2024

Yellow Leaf, Olga Prinku, 2023

Batik – historical context of the process & how it became the method it is today

Batik is a dyeing technique created by incorporating different types of wax as a resist, and it is one of the oldest textile traditions in the world. The wax can be applied in several ways: drawn using a tjanting tool or ladao knife, painted with natural-hair brushes, or stamped onto a surface using carved wooden blocks. Once the wax is applied, the fabric is dyed, and the wax resists the colour, leaving behind patterns when the wax is later removed. This process can be repeated multiple times with different colours to build up complex, layered designs.

Resist dyeing has been used since ancient times in many cultures across both the African and Asian continents. For example, different resist dye techniques can be found in Chinese, Malaysian, Indonesian, Nigerian, and Sri Lankan traditions, each with their own distinctive approaches and motifs. In Indonesia, batik became especially significant, with Java emerging as a cultural centre for the technique. The earliest written description of batik in English appears in The History of Java by Thomas Stamford Raffles, published in 1817. Raffles (1817) observed the process and wrote: “The process of dyeing their cloths is curious, and deserves notice. The parts intended to remain white are covered with wax, and the cloth is then immersed in the dye; after which the wax is removed by boiling, and the operation is repeated for each colour required.” This description highlights both the technical aspect of batik and the fascination it held for foreingers encountering it for the first time. It also demonstrates how batik was already an established practice by the early nineteenth century, deeply embedded in the cultures it could be found.

The patterns created using batik have historically been inspired by the natural world and its cultural significance. Designs often incorporate depictions of plants, animals, and even mythical creatures, reflecting the deep connections between communities and their environments. This relationship between batik and the natural world resonates strongly with my own practice, as I also draw inspiration from nature and its significance in my life. The natural world is not only a source of imagery but also a source of meaning, shaping the way I approach my work and the themes I explore.

In my degree show installation ‘Green 116’, I sought to embody this connection by gathering various batik pieces i had created, each with personal meaning, and combining them to curate a personalised “landscape.” This installation represented the way I view the natural world surrounding me and highlighted the aspects I find especially outstanding within it. Just as traditional batik motifs reflect cultural relationships with nature, my installation reflected my individual perspective, creating a dialogue between personal experience and broader traditions. The act of combining multiple batik pieces into a single landscape also echoed the way batik historically brings together motifs to form larger narratives, whether in ceremonial cloths or everyday garments.

I believe my curation of ‘Green 116’ was unique in relation to traditional batik paintings and the way they are usually displayed. Rather than presenting the pieces flat against the wall, I hung each individual batik on frames protruding from the wall at different depths and widths. This arrangement created an element of three-dimensionality within the installation, further representing the idea that it was made to represent a lived landscape within the exhibition space. By breaking away from conventional display methods, I was able to emphasise the spatial qualities of batik and explore how it could function not only as a surface but also as an environment. This approach allowed viewers to experience the work in a more immersive way, engaging with it as a landscape rather than simply as a series of images. By doing this I was able to highlight the potential of batik to move beyond its traditional role as a textile and become part of a larger installation.

After researching the history of wax-resist processes, I have been inspired to expand my practice further. Traditionally, batik has often focused on figurative depictions of plants, animals, and mythological creatures, but I am interested in incorporating more abstract pattern-making alongside these straightforward depictions. Abstract patterns would allow me to focus more on the colours I want to include in the peripheries of my paintings rather than just the colours of the plant or animal being directly depicted. This shift would open up new possibilities for experimentation, enabling me to explore how colour, line, and shape can evoke mood and meaning even without direct representation.

In addition to abstraction, I am also interested in experimenting with scale and format. Up to now, my batiks have kept to a near-uniform size, but I believe creating works of different sizes and shapes could open up new possibilities for display and interpretation. Larger pieces could invite viewers to immerse themselves more fully, while smaller works might encourage more intimate engagement. By varying the scale of my batiks, I can expand the scope of my practice and explore how form and presentation shape meaning. This experimentation would build on the three-dimensionality I explored in ‘Green 116’, pushing my practice further into the realm of installation and spatial art.

Another area I want to develop is the technical side of batik. Specifically, I plan to experiment with different ratios of soy, paraffin, and beeswax in my batiks. Each type of wax has distinct properties that affect how the dye interacts with the fabric, and by adjusting the ratios I can achieve different effects. Stronger dyes could allow for deeper, brighter colours, while certain wax combinations might produce bolder, more distinct lines and shapes.

Researching about batik’s history has shown me how textiles can serve as a way to explore identity, culture, and symbolism, while also offering rich aesthetic possibilities. By working with batik, I am participating in a dialogue that spans centuries and cultures, and I am continually inspired by the ways in which this technique allows me to explore the relationship between humans, nature, and creativity.

Looking ahead, I am excited to expand my practice through abstraction, experimentation with scale, and technical innovation, building on the long and varied history of batik while also making it my own.

Raffles, T. (1817) ‘The History of Java’, London, United Kingdom: John Murray

Detail of an Indonesian Sarong, Coffee Bean patterned batik

Intricate batik pattern on a Chinese baby-carrying quilt